RON HOWARD AND EDITOR PAUL CROWDER ON NEW JIM HENSON DOC, POSTPERSPECTIVE

Director and producer Ron Howard has made several documentaries in recent years, including the Grammy-winning The Beatles: Eight Days a Week, Pavarotti, Rebuilding Paradise and the Emmy-nominated We Feed People.

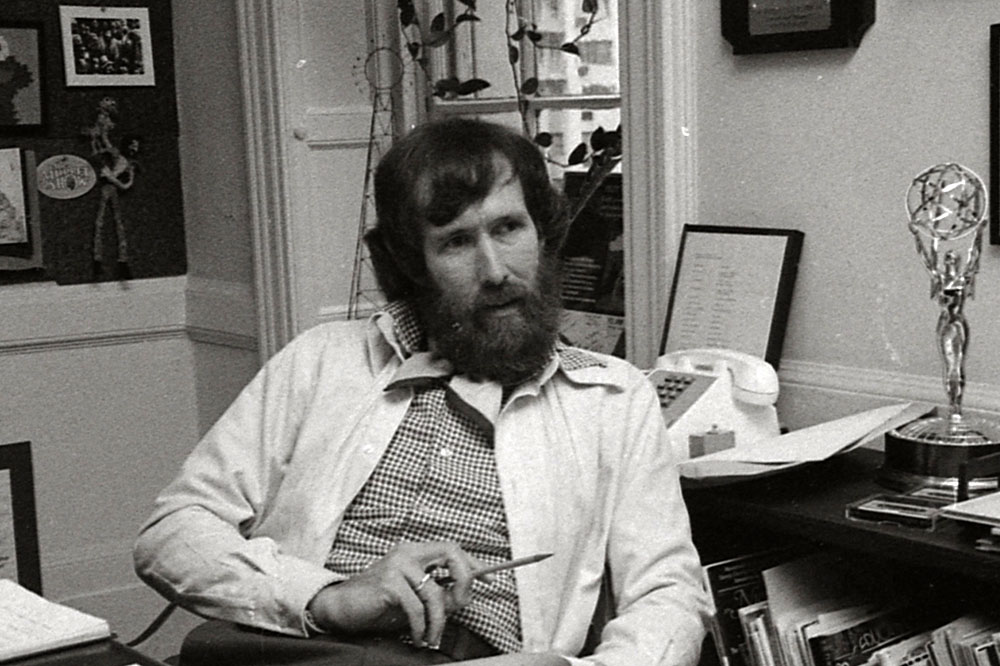

His latest, Jim Henson Idea Man, chronicles the story of artist and visionary Jim Henson, who created such classic Muppets as Kermit the Frog and Miss Piggy and all of Sesame Street’s iconic residents, including Big Bird, Cookie Monster, Ernie (performed by Henson) and Bert (performed by Frank Oz). Henson also directed fantasy films like The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth.

Produced with the full cooperation of the Henson family, Jim Henson Idea Man is an intimate look at Henson’s career and complex personal life. Using never-before-seen personal archival home movies, photographs, sketches and Henson’s personal diaries, as well as interviews with those who knew him best, the film builds a definitive portrait of the iconoclastic artist. It will premiere May 31 on Disney+.

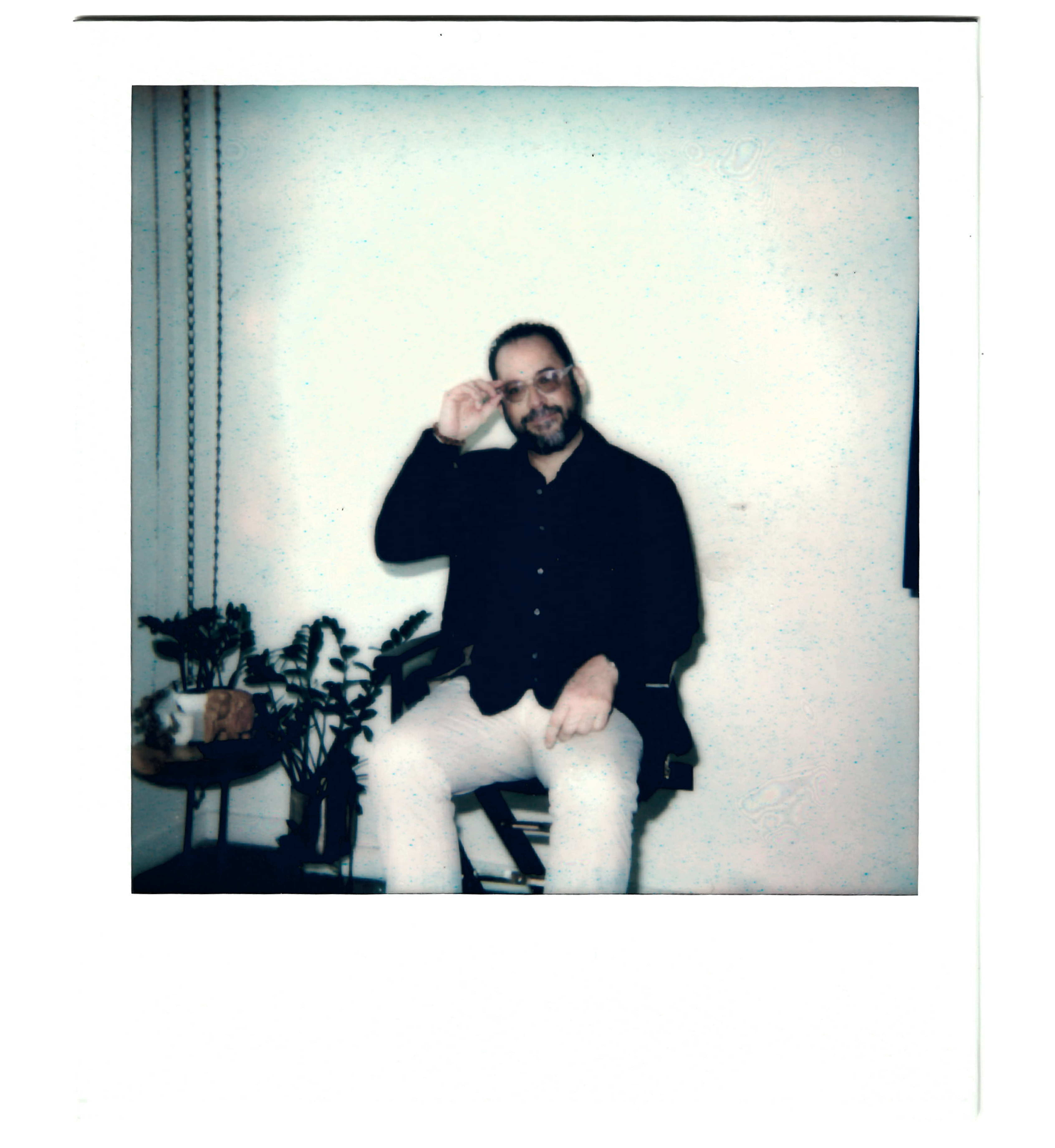

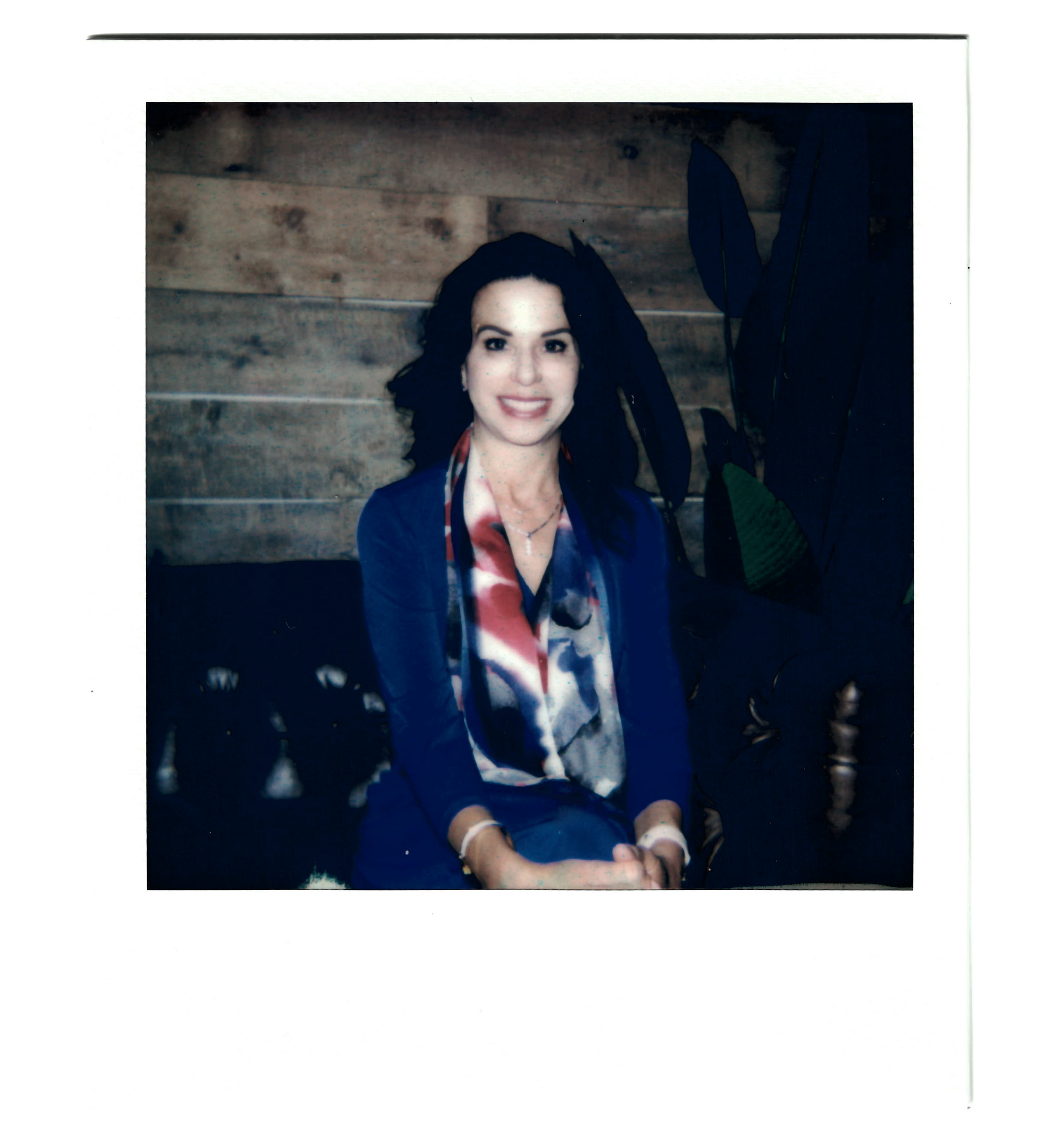

I spoke to Howard and editor/EP Paul Crowder, ACE, who cut The Beatles: Eight Days a Week and Pavarotti, about the project and its challenges. Editor Sierra Neal was also an editor on the doc.

What was the appeal of this project?

Ron Howard: I admired Jim Henson. I met him only briefly, so I had no real personal context, but I had a lot of exposure to his characters. However, when we sat down with the family and I saw the archival footage, I began to recognize how broadly artistic he really was and how there was a voice there. He was kind of an auteur in that even his strange experimental stuff informed the Sesame Street learning pieces that he created. I was fascinated by this restless creativity, this yearning to explore, to create and express himself through the mediums in various ways, and the way that had such an enduring impact on us in straight-on popular entertainment and children’s education. I immediately wanted to get into the story.

Paul, I assume there was no real script that you and Ron had in front of you. It must have been more free form, right?

Paul Crowder: To a degree. We do work within the parameters of how we’ve decided to make the film. We understand the story timeline, and we definitely understand the things we want to talk about. And we had Mark Monroe, a fantastic writer who gives us pages with some interview bites and things that can help. Then we sat and just basically laid out the interviews and started telling the stories.

One of the things that happened early on that was really eye-opening for me was when we went with Ron and the family and viewed all the archival footage at their offices in Los Angeles, and we sat and watched two hours of Jim’s work that was unfamiliar, all his early work in his early films. There was so much style in there; there was so much creativity. There was so much in the way he made the films that we discussed it immediately after the screening. It was like, we have to lean into this. This is the path. We’ve got to try to keep this as “Jim” as we can because look at the energy it brings.

Look at the excitement, the fun, everything. He’s always having fun, always being creative. So that really was a great eye-opener for how we can approach this film. That’s definitely the way we leaned.

How did the idea of using stop motion come about?

Howard: In our first big interview with Frank Oz, we were shooting, and we had the idea of this cube, which was a project of Jim’s — kind of an obscure one that people didn’t know about, but it sort of said something about Jim’s psyche. I thought it was a great idea, so we used it, and it wound up being so helpful. The other thing is that we set up for that first interview with Frank, and he’s so playful and creative himself that I suddenly got the notion of, well, why should we just have you walk to your chair? Let’s do stop motion. Frank loved it. He beamed.

We put up a high camera and set the frame, and he knew just exactly how to play it out. He just did one pass, and then we had the chair come in and swirl around, and it was like, voila! This thing that all of us have been talking about is going to find its way into the film in a very Henson way, stylistically. We’ve been building from there, including some really great creative graphics work by Bigstar and some stop-motion animation work by Screen Novelties, who really were just thrilled to get involved with this.

It was everything I dreamed of in terms of infusing the film with Jim’s slightly zany aesthetic, and it was gratifying to see it come together.

Tell us about the editing workflow.

Crowder: There was just constant media coming in, constant things for us to edit coming through the system. There was also a lot of low-rez media in the beginning, as we had so much from old DVD and VHS sources, so editing in large files wasn’t needed and we had DNX LB ingest.

Sierra just did an incredible job, and that is part of the reason we were able to build the scenes quite quickly. Sierra went through all the footage first of all, and she made all these selects and built reels of ideas of these little sequences based on different obvious stories from the films Labyrinth, the Muppets [from The Dark Crystal] et cetera. So we had those as little building blocks. One of the early scenes we cut — which, sadly, isn’t in the film, but it was a good cut and a good lesson in filmmaking — was one where we were introducing the kids like in Sesame Street.

Cheryl Henson says, “My mom had four kids in five years,” and then four siblings appear — 1, 2, 3, 4 — just like Sesame Street. We just did this whole piece, and suddenly we found the voice, the stop motion, things that had been shot in the first interview, and that was working, and then this scene was working, and we really felt like, “Hey, I think we’re on the right path here. This is the path to follow. Let’s really elaborate on the cube.” So every time we started shooting the interviews after that, we had a lot of other things in mind about how this cube could be a magical place and anything can happen in this cube. Kind of like the synopsis for the project that Jim did himself.

Howard: Despite all the virtual, we did have some really important marathon sessions, as we always do, where we would just get in the same room and run it, stop and go and discuss it. And those were really important and informed ongoing interviews because we’d begin to recognize that we wanted to delve a little deeper in one area or another.

Paul, did you do many sound temp and effects temps in the edit?

Crowder: Yes, we did some basic stuff. We worked with Bigstar early on, and they gave us some basic ideas for what to look at and work within the cut. And talking about some of the challenges with these limited interviews that were available for us, two of the Jane [Henson’s wife] interviews were done on a Dictaphone or something sitting on the table for a different project. It wasn’t for an audio thing; it was more like for a book. So the sound quality was really poor, and it was very difficult to hear but what she was saying was fantastic.

It was the same with a couple of Jim’s interviews. So we toyed with lots of ideas on how to improve the sound. At one point we even considered using AI, as Jim had so few interviews. But he wrote down so many great things, so we thought that maybe AI could say it in Jim’s voice, but it just didn’t feel right. It didn’t work. You could tell.

What about the DI? You had all this different material from all different eras, so that must’ve been really important, right?

Howard: Very, yeah. We did it at Harbor with colorist Roman Hankewycz, and we spent probably more time on this DI than any of the other docs that I’ve worked on for the reason you mention. And in this case, we had a timeline. Paul was here in LA, and I was on the East Coast, but we were all working together technically.

Crowder: We were watching the online in a studio in LA and another in New York, and as we were looking at it, the thing that was immediately apparent was that the video footage, especially anything that was from the ‘90s and the late ‘80s, was really breaking down, and especially on the big screen.

It was very problematic, and it wasn’t something we knew. It didn’t look great when we were working with it, but it never looked that bad until we got it up in full-rez. So that was a big thing that we had to fix. I think they did an incredible job in the end on fixing this stuff. We did as much as we could on all the restoration work.

The family gave you access to a lot of archival material, but was it difficult getting Jane, his ex-wife, and Lisa, his daughter, involved in the actual documentary?

Howard: The big challenge was in getting Jim and Jane’s voices into the film because they were reticent to ever do much publicity. They didn’t do a lot of interviews, either of them — Jim, not that many, and Jane, even fewer. So it was important to try to keep this in their voices and have them tell their own story as much as possible. That required a lot of research and a lot of important editorial choices, which Paul can speak to, to try to keep them in the film.

Very late, we found another key interview with Jim and a bunch of great photos of Jane, and it was so interesting how that unlocked for us a kind of pathway to help audiences understand and relate to them as characters in a relationship, as artists in a company and as individuals on their own journeys.

How would you sum up the whole project? Did you learn anything that really surprised you about Jim, who died so young at 53?

Howard: His restless creativity that drove the innate sense he had that time was fleeting and how he wanted to maximize every moment… I found that very interesting. It was present in him and in his life. He didn’t necessarily speak about it directly a lot, but people witnessed it in him.

One of the challenges was to get to understand the Jim and Jane relationship. Look, it’s not a tragedy. Their marriage didn’t make it, but their family did. They did it well, like they did most things in their life, but it was indicative of some things that were very specific to him and her and the family. We wanted to get that across in a way that wasn’t at all melodramatic but was an honest reflection of an aspect of success and ambition — how a couple can come together and mean so much in terms of launching the idea of the Muppets and launching their family and then still grow apart and recognize that that’s an aspect of the way the world works.

As joyous and successful as they were, they weren’t immune to those kinds of struggles. The family was helpful and cooperative, and that’s why, again, it was so important to get Jane’s voice into this movie. She was so significant in the foundation of everything that we appreciate and respect, and yet she just was never terribly interested in talking about it. In the end you realize the enduring reach and power of his creativity, and it was all the more important to me because I want audiences to realize how a total creative life — with all the experimentations, the successes, the disappointments, the half-finished things, the fully fledged ones — can all add up to something, and the result can be something that’s so memorable and important for us, but it’s never quite as easy or as uncomplicated as it might seem.